In December 2024, astronomers in Chile spotted a new asteroid streaking through the sky, which they named 2024 YR4. What’s significant about this 100m-wide space rock is that it has a small chance of hitting Earth in 2032.

Since its discovery, the asteroid’s probability of an impact with our planet has gone all over the place. At one point, the risk rose as high as 3.1%. This may not sound like a lot, until you realise that that is a 1 in 32 chance of collision.

As of February 21 2024, the European Space Agency’s (Esa) Near Earth Object Centre predicts the collision probability to be just 0.16%, which is a 1 in 625 chance – a huge difference. So why is there such a huge variability in these predictions? And is there really a need to be concerned?

Asteroids are left over remnants from the formation of the solar system, mostly rock, but also metallic, or icy bodies that tend to live in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Space agencies like Nasa and Esa independently monitor and track over 37,000 near Earth asteroids (NEAs). These NEAs are those that come within 1.3 astronomical units distance of Earth, where 1 astronomical unit is the average distance between the Earth and Sun. Around 1,700 objects are considered to have an elevated risk because they make a relatively close approach to Earth at some point in the future. They are said to have a non-zero probability of colliding with our planet.

Now it’s estimated that 44,000 kg of space rock hits our planet every year, but most of it is dust or sand grain sized particles that will burn up in the atmosphere, creating the beautiful streaks in the sky that we know as shooting stars.

Rarely do these objects make it to the Earth intact as a meteorite and it’s even rarer to have a cataclysmic impact, like the 10km wide object that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. The last major asteroid event in recent history was the 18m wide meteorite that hit Chelyabinsk in Russia in 2013.

The fireball turned night into day and released an estimated 500 kilotons of energy (equivalent to 500,000 tonnes of TNT) as it explosively broke apart in our atmosphere. Around 1,500 people were injured – many through the sonic waves shattering windows.

Current estimates for 2024 YR4 suggest it to be up to 100m in size. It is capable of releasing about 7.8 Megatons of energy (equivalent to 7.8 million tonnes of TNT explosive), which is much more than Chelyabinsk. If such an asteroid were to hit the centre of London you could expect over 2 million fatalities. But the effects would be felt over a larger area.

The impact would have a “thermal radiation radius” of 26 km. Within this radius, the heat from the impact would be so intense it would cause third degree burns. So despite the small probabilities, there’s no question that this asteroid should be monitored and tracked closely.

Nasa has also reported a very small chance that 2024 YR4 could collide with the Moon instead. This would pose no threat to people on Earth, but would generate a sizeable impact crater on our planet’s only natural satellite.

No simple answers

Tracking an asteroid turns out to be more complex than you might think. Unlike stars and galaxies, asteroids don’t emit light so are notoriously difficult to spot. This faintness likely contributed to why 2024 YR4 4 eluded detection up until so recently.

In addition, the shape of the asteroid, and its albedo – which measures how reflective the asteroid is – is still highly uncertain, further complicating the prediction of its future path. The albedo of the asteroid not only tells us about the composition of the asteroid, but can inform us of interactions with the Sun.

A darker asteroid will absorb more light, heating up any gases within the asteroid. When released, these gases can act like jet thrusters, altering the trajectory of the asteroid. A more reflective asteroid, might incur more radiation pressure from the Sun. This pressure can actually push it in another direction to the one it was previously going in.

The current estimates of YR4’s albedo are between 0.05 – 0.25, with 0 being completely matte, and 1 being completely reflective, so the margin of uncertainty is wide. As you might expect, the shape of the asteroid will also affect the direction in which these forces act and the resulting trajectory of the object.

Current trajectory estimates assume a spherical asteroid, with a typical density for an S-type asteroid (a common type of rocky asteroid). The asteroid 2024 YR 4 has very little chance of being spherical (that shape tends to be seen in bigger objects with stronger gravity) and we don’t know what exactly it’s made from. Future observations, potentially including those from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), aim to refine our understanding of the asteroid’s shape.

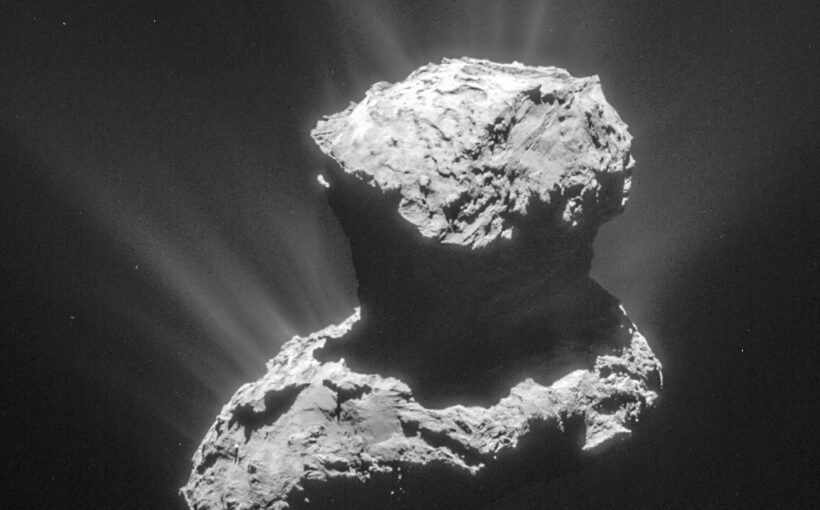

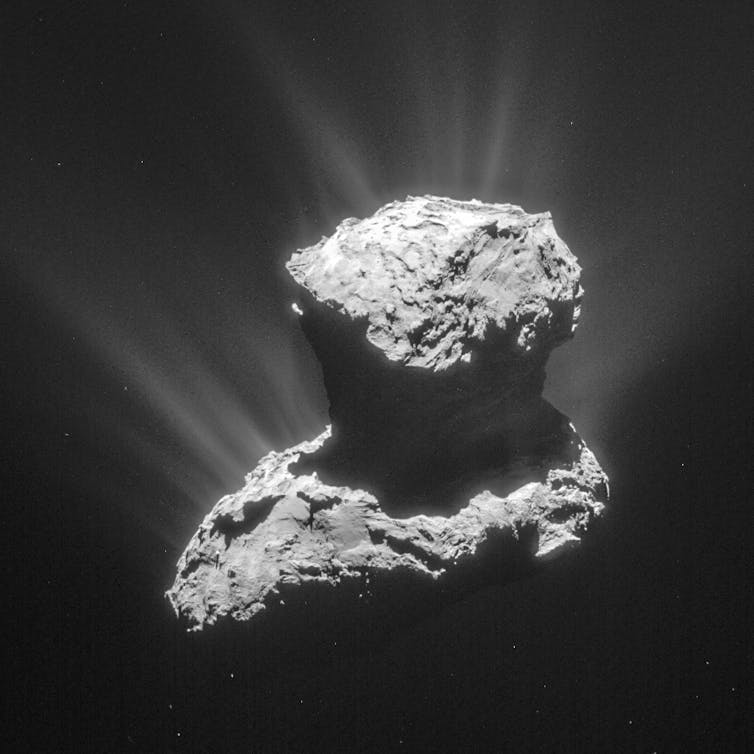

However, past discrepancies between predictions of the comet 67P, as seen by the Hubble telescope from far away, versus its actual shape captured by the Rosetta spacecraft, which explored it up close, demonstrate the limitations of our predictions.

Spectral imaging (which measures different colours of light to give an indication of composition) will hopefully allow us to better understand what type of material is on the surface of the asteroid and whether there could be volatile gases hiding beneath it that could affect its future path.

Given that the projected Earth impact is a mere seven years away, the window for sending a spacecraft to try and divert it away from our planet, as successfully demonstrated by Nasa’s Dart mission in 2022, is rapidly closing. While other options such as detonating a nuclear weapon near the asteroid to deflect its path remain theoretically possible, they come with significant risks and ethical considerations. For instance, instead of diverting the asteroid, a nuclear explosion could break it into two or more pieces, which could then collide with Earth in distinct locations.

There is a possibility that the asteroid could be nudged off course by collisions with other space rocks. It’s also likely that, if it does collide with Earth, it won’t hit a populated region, since the majority of our planet is uninhabited. However, it should be possible to evacuate people should it threaten a populated area.

For now, the best thing we can do is track the asteroid with more observations, refining its trajectory, properties and impact probability estimates as more data becomes available. As we have already seen over the past few days, the predictions are likely to continue changing.

![]()

Maggie Lieu has received funding from STFC.