If the object of your affection were to suggest that a “platonic” relationship might be of more interest to them, your heart might sink a little. The common understanding of Platonic love, so called after the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, is that it indicates a relationship of strong affection from which sex is excluded. But there’s potentially much more to the concept of Platonic love than the absence of romantic or physical passion.

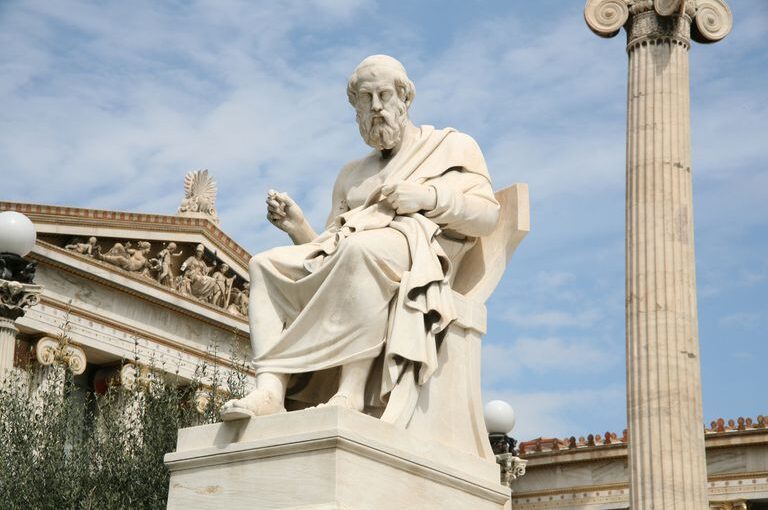

The term is derived from Plato’s writing on the topic of love in the Symposium, a work composed in the early fourth century BC. It’s set at a dinner party in Athens that supposedly took place much earlier in 416 BC, when a playwright called Agathon won first prize for his tragic drama.

Agathon threw a party – symposium in Greek means “drinking together” – where everyone over-indulged. So the following night the partygoers, including the philosopher Socrates, decided that instead of drinking they would give speeches in praise of the god of love, Eros (whence comes the word “erotic”).

In the course of the party, the comic poet Aristophanes offers a humorously extravagant story about the origins of love:

Once upon a time human beings were duplicates of what we are today, with four arms, four legs, and two faces. These double-humans came in three types, male-male, female-female, and male-female. They were over-powerful beings who threatened the gods – so Zeus decided to split them in half. Now we’re just halves of a whole, and each half desperately seeks its matching half in a quest for completion. This is what we mean by love.

Humour aside, Aristophanes’ tale accounts for both sexual orientation and why human beings may feel incomplete alone.

There’s great thoughtfulness and variety in the Symposium. In addition to this comic representation of love as literally “seeking our other half”, Plato reports four speeches given by participants, followed by a presentation by Socrates, and finally an extended contribution by the flamboyant Alcibiades, who bursts in late on the gathering.

For ancient Greeks, love was literally divine. The notion that love is a god (Eros) or goddess (Aphrodite) distinguishes many of the speeches in the Symposium. Another culturally distinctive feature is that the party consists entirely of men, who tacitly acknowledge that love is to be thought of as homoerotic.

In ancient Athens, heterosexual relations were rarely seen to involve an intellectual dimension. Women and girls were generally not educated, so the notion of intellectual engagement as a component of a relationship was something reserved for love between men, although Plato’s propositions about love don’t exclude (as Aristophanes’ tale shows) love between the sexes or between women.

In Plato’s day, Athens’ rival city Thebes had established a unit of warriors, the Sacred Band, consisting of 150 pairs of male lovers. The first speaker, the young aristocrat Phaedrus, argues that an army of this kind will be invincible, because men will always strive to show courage in front of the partner they love.

He takes sexual love for granted in arguing that love “inspires lovers to act nobly in matters of life and death”. The following speaker, Pausanias, makes a distinction between true love and sex, insisting that the latter should be reserved for committed relationships.

Other speakers offer more abstract views of love – as a force of universal harmony, or (as Agathon argues) a stimulus to artistic creativity. Socrates then offers to “tell the truth about love”, recounting how Diotima (a fiction evidently based on a real woman, Aspasia of Miletus) had taught him that love begins with physical desire but leads on to “higher” forms such as love of knowledge, beauty, and truth.

The final speech is given by the drunken latecomer to the party, the playboy politician Alcibiades, famously beloved of Socrates. The most handsome youth of his day, he describes how he once tried in vain to seduce the older man. Socrates was not interested because – as he argued a true lover should be – he was keener on improving the young man’s soul through philosophy than being gratified by his body.

Properly understood, then, Platonic love is not about the negation of passion but about its elevation and transformation. This means it cannot be simply narcissistic. Aristophanes’ myth of the original human beings seeking a similar matching half is challenged by Socrates’ doctrine.

Love’s aim, we eventually learn, is not to complete us, but to inspire us to grow creatively in relation to another person. Not to guide us to love our mirror image, but to lead us to educate and be educated by another person to become the highest version of ourselves.

This invites us to think about relationships in terms of shared aspirations. From this point of view, Platonic love means focusing on what lies beyond the relationship itself, on the ideals that connect those who truly love each other.

In practice, one might conclude, the highest form of love is a partnership in which two people are united by a common creative quest. Such love is not passionless, but a powerful force that begins with physical desire but ends with its transcendence.

To love Platonically is to see in another person not just what they are, but what they may be inspired to become, and to climb together toward something greater than one might attain alone.

Seen in this light, the quest for our “matching half” proposed by Aristophanes, if only in jest, cannot be the answer. And though we may not be wholly satisfied with any of the views expressed in the dialogue, the aim of the Symposium is surely to invite us to continue the conversation.

![]()

Armand D’Angour does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.