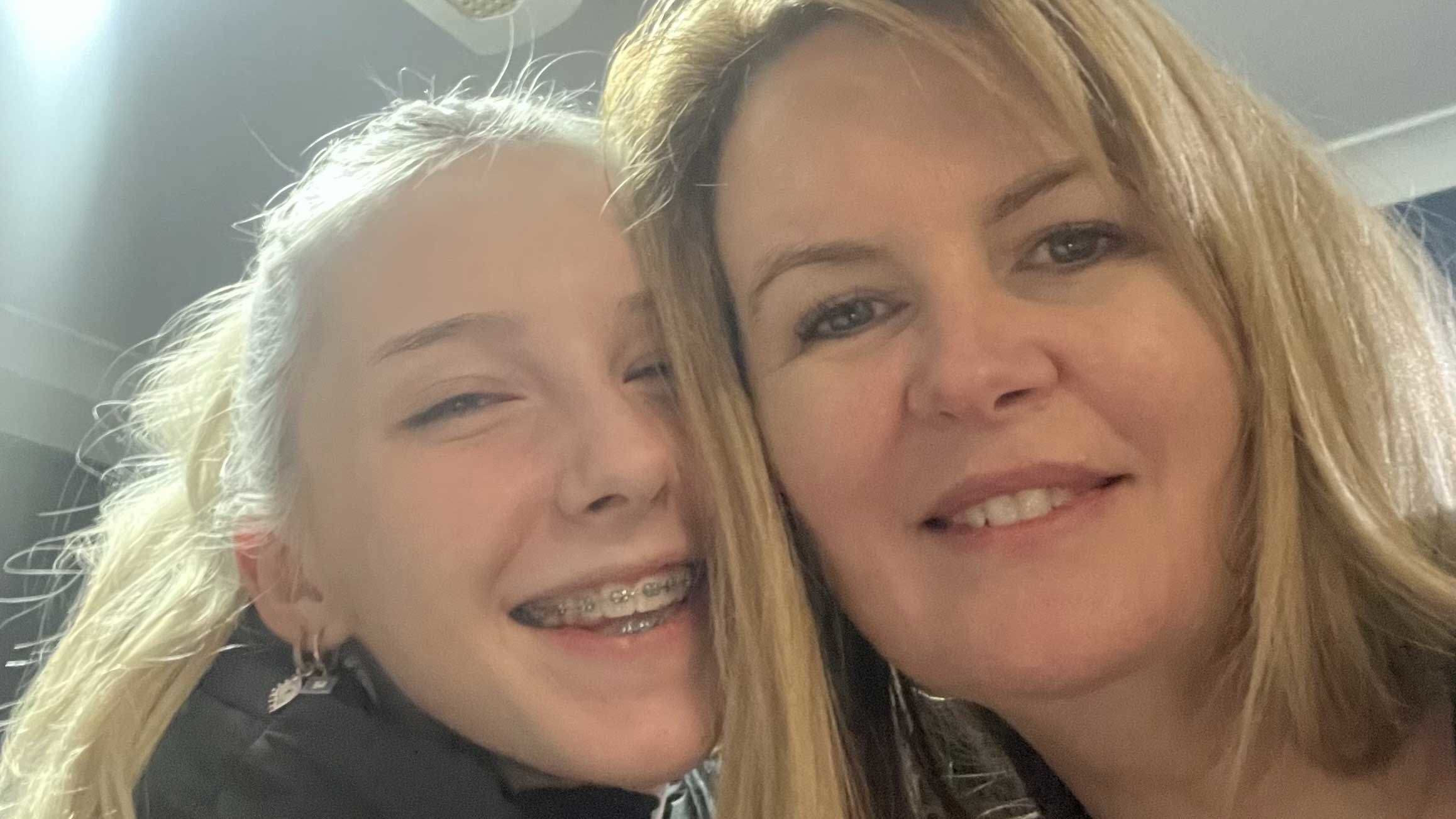

Chelsea Bagnall has lived with excruciating pain for almost as long as she can remember.

As a child, she was sick on and off with urinary infections, bouts of vomiting and bowel issues.

Four years ago, when she was 15 years old, Chelsea's health took a sudden and scary nose dive.

The bouts of vomiting became a daily occurrence and she began experiencing fainting spells. Chelsea's weight plummeted to 40 kilograms, while her body mass index (BMI) was sitting at just 13.

READ MORE: Mystery after bundle of cash found washed up in surf

Instead of receiving answers, Chelsea was misdiagnosed with an eating disorder and placed in an inpatient program where she was force-fed for a year.

Now, after years of suffering, Chelsea, 19, finally has the correct diagnosis: Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome (MALS) and Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome (SMAS), two rare conditions that compress major arteries and make eating unbearably painful.

In 2021, doctors were so concerned about her weight that Chelsea was admitted to a NSW hospital.

There, she was immediately fitted with a nasal feeding tube in an attempt to stabilise her weight.

"I was in there for a couple of days before a psychiatrist came to talk to me, but I realised quite quickly that I wasn't in a normal hospital room," Chelsea said.

"I was put in a room with three other girls who all had tubes in their faces as well. I didn't quite understand at the time that I was already being stereotyped into something that I wasn't even aware of."

When she was seen by a psychologist, Chelsea said she was asked leading questions about her eating habits.

"She was asking me questions, like, 'What do you think of your body image? Have you ever made yourself vomit? Do you starve yourself?'" Chelsea said.

"Obviously, I answered with, 'No, I've never starved myself, I've never made myself vomit. I've never wanted to be thin'.

"I quite clearly said to her, 'I want to put on weight. I want to be healthy'."

Despite Chelsea's insistence that she did not have an eating disorder, doctors diagnosed her with avoidant, restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) and placed her in an eating disorder program, where she would spend months at a time.

Her mother, Emma Bagnall, told 9news.com.au she felt also pressured to believe in the diagnosis.

"They pulled me aside and had separate conversations with me. They told me, 'She's going to do anything she can to get out of this. She's going make excuses. She's gonna fight to not be here'," Emma said.

"There were tears, and she was begging me to take her home, and I'd have to calm her down."

READ MORE: Peter Dutton quizzed on Coalition tax policy after budget handed down

As part of the program, Chelsea was weighed every morning and put in a room to eat her food in front of hospital staff with a timer.

"If we didn't finish in time the food was thrown out," Chelsea said.

"I was in there, and I realised these girls didn't have the same issues with eating as me, they weren't in excruciating pain.

"They were reluctant, and refusing at first, but eventually they gave in, because they realised they don't have a choice. I was trying to eat, but I couldn't keep up. Before I knew it, the alarm would go off and my food was snatched away from me."

When she did not finish her food in time, Chelsea said she was given a liquid supplement to drink, which she would often immediately vomit up.

While other patients in the eating disorder program would recover and go home, Chelsea would be in the hospital for long periods of time, attending school there.

Emma said the treatment her daughter received was "inhumane" but just as worrying was the lack of other tests done to get to the bottom of her illness.

"They should have had her seen by a rheumatologist, endocrinologist, and gastroenterologist. They didn't," Emma said.

"No doctors did any tests, no one consulted her about anything else. There was no further investigation."

Things did not change for Chelsea until the family moved to Canberra, where confused doctors confirmed she showed no sign of having an eating disorder and began running gastrointestinal tests.

However, the breakthrough really came last Christmas during a visit to a GP, who had stepped in when Chelsea's regular doctor was away.

The GP, Emma said, pulled a stethoscope out and listened to Chelsea's stomach, before commenting that he could not hear any movement.

He ordered a CT angiogram, and while the mother and daughter were initially sceptical, it proved to be the missing link to the puzzle.

The scan showed a compression on Chelsea's left renal vein, leading to the diagnosis of Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome (SMAS).

An ultrasound later showed compressions on Chelsea's celiac artery as well, a sign pointing to Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome (MALS).

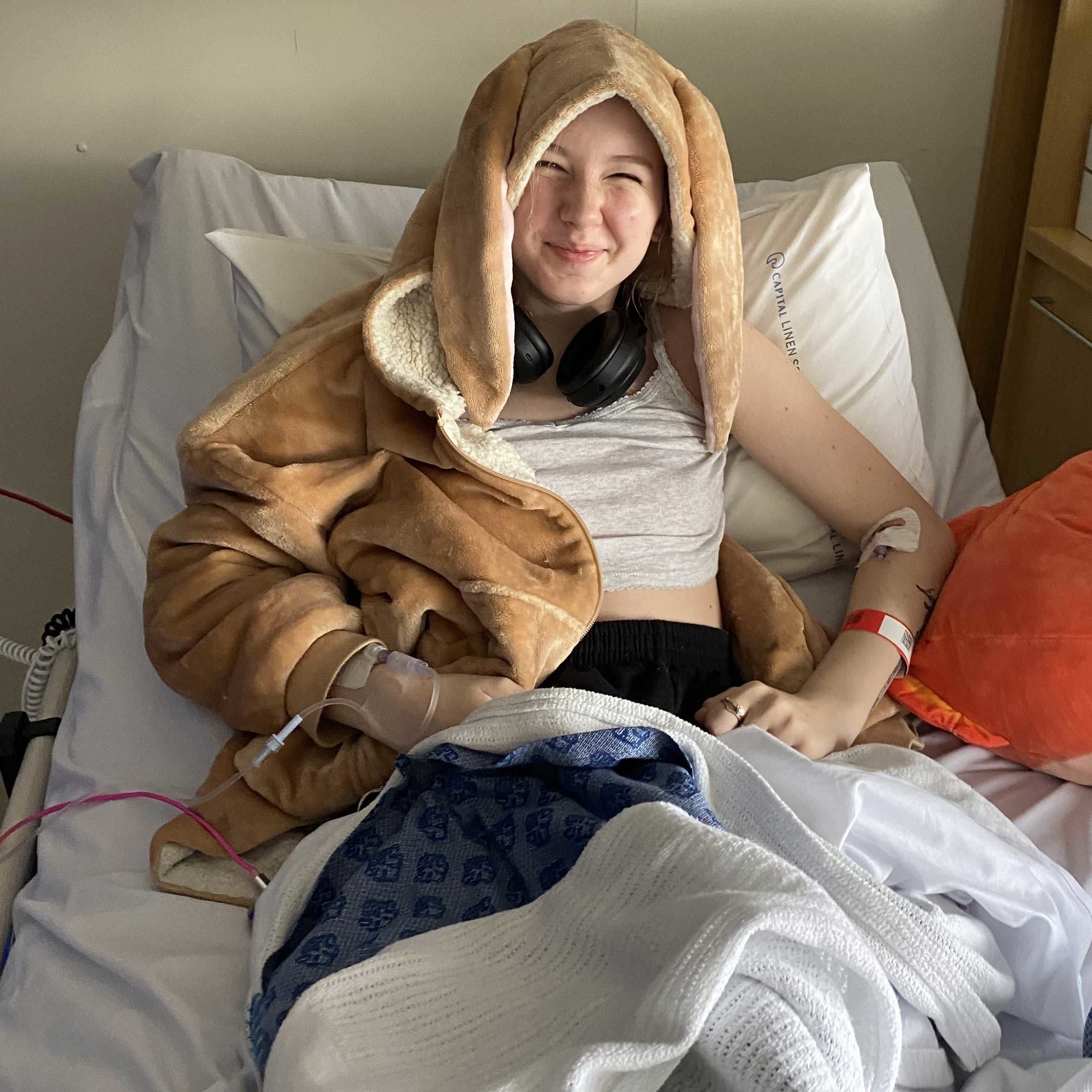

Further testing has shown three areas needing surgery and Chelsea is set to finally get the help she needs with an operation in May.

Canberra vascular surgeon Gert Frahm-Jensen said vascular compression syndromes, such as MALS and SMAS, were a controversial subject.

"They are considered very rare, although the reality is that they're probably more common than we think," Frahm-Jensen, an Associate Professor at the Australian National University's School of Medicine and Psychology, said.

"What makes it extra tricky is that sometimes patients have scans that show vascular compression but no symptoms, other times they have relatively mild compression but significant symptoms."

While roughly one fifth of the population had some sort of compression of their celiac artery consistent with MALS, most of these people were not affected by chronic abdominal pain or trouble eating, Frahm-Jensen said.

Adding to the difficulty with diagnosing MALS was the fact that there were many causes of stomach pain which were far more common, including gallbladder or pancreas problems or inflammatory bowel disorders.

"It becomes in many cases a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning you've ruled out everything else," Frahm-Jensen said.

Despite scepticism from some doctors about whether MALS and SMAS were real conditions, about 70 per cent of people who underwent surgery for MALS and SMAS showed an improvement in symptoms afterwards, he said.

Chelsea said she hoped surgery would give her a chance to live a normal life, but the experience of being left to suffer in pain for years by the medical profession had left her scarred.

To those struggling with undiagnosed health problems, Chelsea has a message: "You know your body. You know if something's wrong. Don't stop advocating for yourself, no matter how hard it gets, no matter how much you're dismissed, no matter how much you're gaslit into believing that you're fine.

"If you know there is something wrong, fight for it, because you won't get anywhere unless you do."