In an increasingly polarised world, the arts and humanities play a key role in sustaining democracy. They foster critical thinking, open dialogue, emotional intelligence and understanding across different perspectives, all of which are essential for a healthy democratic society. Also, people who participate in cultural activities are much more likely to engage in civic and democratic life.

Yet the way the arts are funded differs widely from country to country, especially in times of economic hardship or significant change. During and after the pandemic, for instance, some EU countries increased public spending on culture, while others made significant cuts.

The reasons for these contrasting attitudes are many, from local cultural values, to shifting economic priorities and politics. But at their core, different funding strategies express different attitudes towards two questions: what contribution does art make in times of crisis? And how do communities express their experiences of uncertainty?

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

As I argue in my recent book Facing Crisis: Art as Politics in Fourteenth-Century Venice, the medieval city of Venice provides a remarkable historical example for addressing these questions.

Between the sixth and 12th centuries, Venice grew into an independent city-state ruled by an elected council and an elected head of state, called the doge.

Set on an island, the city lacked some of the resources necessary to its survival, so it quickly established strong maritime trade networks across the Mediterranean. It gradually developed into an international merchant empire, acquiring strategic territories along the eastern Adriatic Coast, Greece and the Aegean Sea.

By the mid-14th century, Venice was a leading global power. Yet, between 1340 and 1355, the city also faced famine, plague, a violent earthquake and fierce military conflicts with Genoa and the Ottomans.

Internally, Venice tackled dramatic political tensions (including a coup and the public execution of a doge in 1355), as non-noble citizens were gradually excluded from public office. Strikingly, it was during this period of acute crisis that the government initiated a series of ambitious artistic projects in the state church of San Marco.

A new baptistery and a chapel dedicated to Saint Isidore of Chios were lavishly decorated with mosaics. In addition, the high altar, which provided religious focus for the faithful, was revamped. This included turning its uniquely precious golden altarpiece into spectacular moving machinery that would open and close to reveal different images daily, and on feast days.

These projects, which required substantial public spending at a time of financial strain, hardly represented business as usual for Venetian policymakers. Instead, they were a central part of the government’s wider response to crisis.

On one level, these new projects revealed the range of pressing concerns that engulfed the Venetian government and people at the time. The painted altarpiece displayed on the altar of San Marco on non-festive days exhibits an emphasis on human suffering, miracles and saintly interventions that may relate the need for reassurance in uncertain times.

The bloody conflict against Genoa likely influenced the dedication of a chapel to St Isidore. The saint’s body was transported to Venice from the Greek island of Chios, a vital Genoese stronghold in the 14th century. To the people of Venice, the physical presence of St Isidore’s relics in San Marco provided reassurance and the promise of protection and victory as their state engaged in a risky conflict.

Finally, uncertainty about the nature and boundaries of citizenship and political authority – which the expansion of Venice’s overseas territories transformed into an ever more urgent problem – offer a valuable way to interpret the imagery in the baptistery. Here the apostles are rendered in mosaic as they baptise the “nations of the earth”, offering an idealised image of union in diversity.

Yet, on another level, the projects sponsored by the Venetian government during this period represented the active exercising of the political imagination. In ways that some of us may find alarmingly familiar, Venice’s ongoing instability made traditional approaches to decision-making, communication and control ineffective in dealing with the challenges it faced.

Venice’s governors responded to the crisis which threatened the very survival and stability of the city and its political foundations with a wide-ranging strategy of legal, institutional and historical revision, aimed at clarifying the nature and functions of the Venetian state.

The government reaffirmed Venice’s civic laws and reorganised its international treaties. The authority of the doge was progressively restricted, and over time, the government clarified the rules for holding public office. The first official history of Venice was completed in 1352.

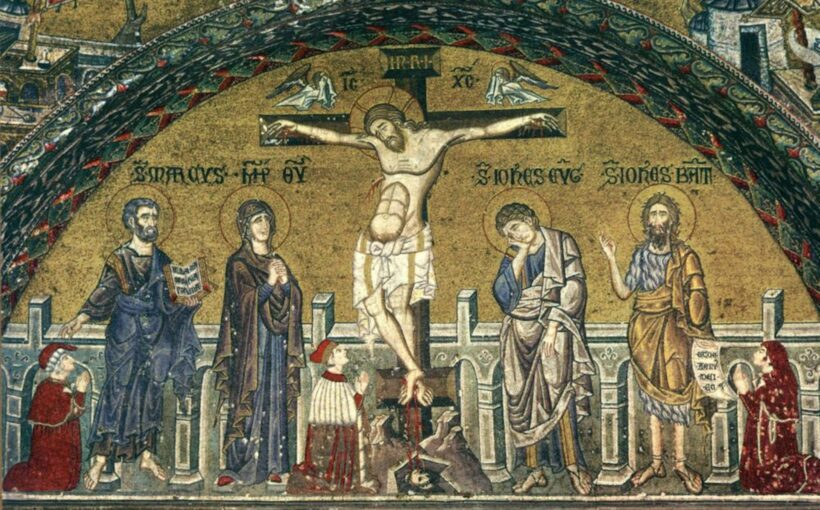

In this context, the San Marco projects did not merely express the anxiety of the Venetian people, or their hopes for renewed stability. They represented the establishing of a new political landscape, which was envisioned most clearly on the east wall of the baptistery.

Three secular figures – a doge and two officers – are depicted as kneeling supplicants within a monumental mosaic of the crucifixion (see the main headline image above). Blending the sacred with the secular, this image offered an abstract “state portrait” that simultaneously expressed a political reality and suggested a new political ideal.

The mosaic now rendered Venice’s doge as a humble ruler, and it represented the business of government as a collective enterprise. In so doing, this image articulated a new vision of government as public service and shared responsibility. This idea, which developed through political reforms in Venice and from broader debates in other medieval Italian city states, has went on to influence western approaches to government and public life to this day.

Venice’s state-sponsored artistic commissions were not propaganda in the modern sense. Instead, they offered a compelling visual reflection on the nature of leadership and the necessary limits of authority. They kindled a new vision of government that enabled Venice to navigate one of the most turbulent phases of its history – reminding us, too, of the power of the arts to inspire and imagine new futures in difficult times.

![]()

Stefania Gerevini does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.