Optical illusions are great fun, and they fool virtually everyone. But have you ever wondered if you could train yourself to unsee these illusions? Our latest research suggests that you can.

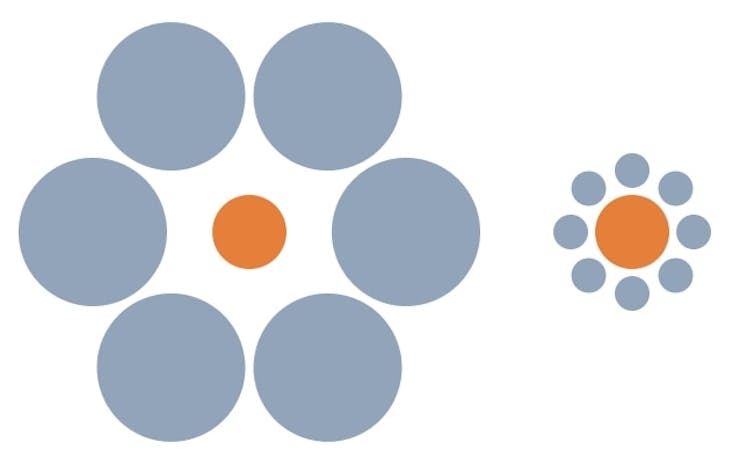

Optical illusions tell a lot about how people see things. For example, look at the picture below.

The two orange circles are identical, but the one on the right looks bigger. Why?

We use context to figure out what we are seeing. Something surrounded by smaller things is often quite big. Our visual system takes context into account, so it judges the orange circle on the right as bigger than the one on the left.

This illusion was discovered by German psychologist Herman Ebbinghaus in the 19th century. This and similar geometrical illusions have been studied by psychologists ever since.

How much you are affected by illusions like these depends on who you are. For example, women are more affected by the illusion than men – they see things more in context.

Young children do not see illusions at all. To a five-year-old, the two orange circles look the same. It takes time to learn how to use context cues.

Neurodevelopmental conditions similarly affect illusion perception. People with autism or schizophrenia are less likely to see illusions. This is because these people tend to pay greater attention to the central circle, and less to the surrounding ones.

The culture you grew up in also affects how much you attend to context. Research has found that east Asian perception is more holistic, taking everything into account. Western perception is more analytic, focusing on central objects.

These differences would predict greater illusion sensitivity in east Asia. And true enough, Japanese people seem to experience much stronger effects than British people in this kind of illusion.

This may also depend on environment. Japanese people typically live in urban environments. In crowded urban scenes, being able to keep track of objects relative to other objects is important. This requires more attention to context. Members of the nomadic Himba tribe in the almost uninhabited Namibian desert do not seem to be fooled by the illusion at all.

Gender, developmental, neurodevelopmental and cultural differences are all well established when it comes to optical illusions. However, what scientists did not know until now is whether people can learn to see illusions less intensely.

A hint came from our previous work comparing mathematical and social scientists’ judgements of illusions (we work in universities, so we sometimes study our colleagues). Social scientists, such as psychologists, see illusions more strongly.

Researchers like us have to take many factors into account. Perhaps this makes us more sensitive to context even in the way we see things. But also, it could be that your visual style affects what you choose to study. One of us (Martin) went to university to study physics, but left with a psychology degree. As it happens, his illusion perception is much stronger than normal.

Training your illusion skills

Despite all these individual differences, researchers have always thought that you have no choice over whether you see the illusion. Our recent research challenges this idea.

Radiologists need to be able to rapidly spot important information in medical scans. Doing this often means they have to ignore surrounding detail.

Radiologists train extensively, so does this make them better at seeing through illusions? We found it does. We studied 44 radiologists, compared to over 100 psychology and medical students.

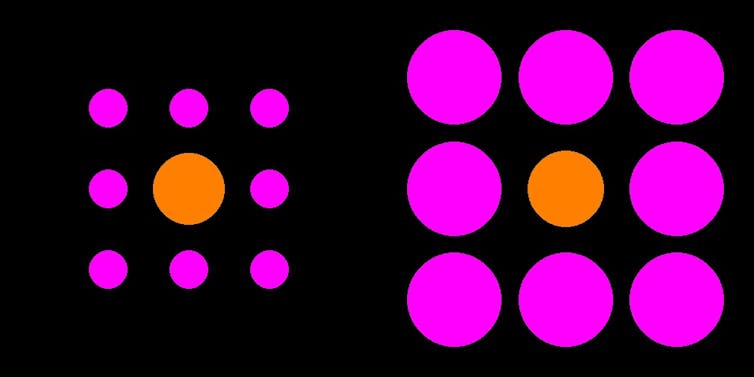

Below is one of our images. The orange circle on the left is 6% smaller than the one on the right. Most people in the study saw it as larger.

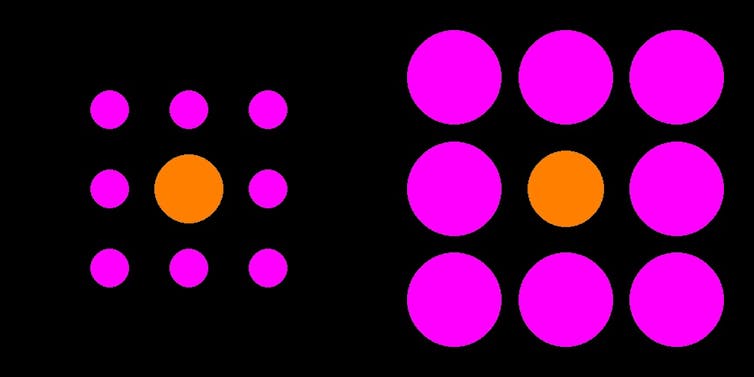

Here is another image. Most non-radiologists still saw the left one as bigger. Yet, it is 10% smaller. Most radiologists got this one right.

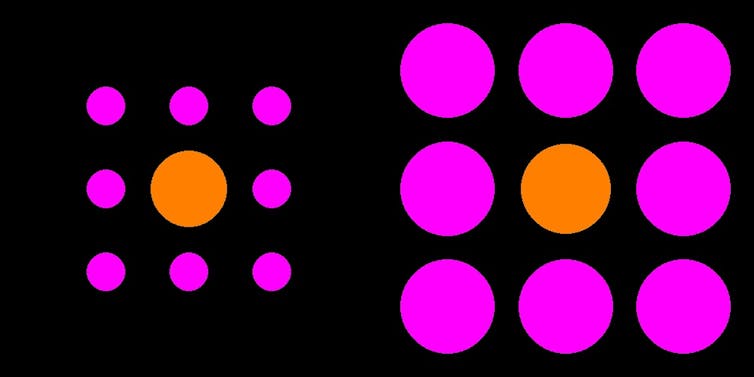

It was not until the difference was nearly 18%, as shown in the image below, that most non-radiologists saw through the illusion.

Radiologists are not entirely immune to the illusion, but are much less susceptible. We also looked at radiologists just beginning training. Their illusion perception was no better than normal. It seems radiologists’ superior perception is a result of their extensive training.

According to current theories of expertise, this shouldn’t happen. Becoming an expert in chess, for example, makes you better at chess but not anything else. But our findings suggest that becoming an expert in medical image analysis also makes you better at seeing through some optical illusions.

There is plenty left to find out. Perhaps the most intriguing possibility is that training on optical illusions can improve radiologists’ skills at their own work.

So, how can you learn to see through illusions? Simple. Just five years of medical school, then seven more of radiology training and this skill can be yours too.

![]()

Martin Doherty received funding from the British Academy/Leverhulme Trust who partially supported this work. He continues to receive funding from the Leverhulme Trust.

Radoslaw Wincza does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.