From a very young age, we’re socialised to view the world as being made up of “goodies” and “baddies”. When you’re a child fooling around with your friends in the playground, nobody ever wants to be the baddy. And when it comes to dressing up, everybody wants to be Luke Skywalker – not Darth Vader.

This oversimplified way of viewing the world as being made up of right and wrong or good people and bad people doesn’t dissipate as we grow older. If anything, it tends to solidify as we form the social identities that define who we are in adult life.

This is particularly the case when it comes to our political identities and, specifically, the partisan identities and loyalties that individuals attach themselves to.

Partisanship is one hell of a powerful force. Not only does sticking a party label under a candidate determine whether we support them or not – often regardless of what the individual candidate actually stands for – but it also shapes how we view the state of the country and economy. Note how Democrats’ view of how the US economy was doing tanked the day Donald Trump took office, while Republicans’ positivity about the same economy spiked.

Want more politics coverage from academic experts? Every week, we bring you informed analysis of developments in government and fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our weekly politics newsletter, delivered every Friday.

Our partisanship can also affect who we choose to socialise with, who we share a beer with, and who we date. There is even evidence that it affects who gets hired and who doesn’t. Knowing who your neighbour votes for and if they vote for “your team” shapes your view of them as good or bad.

In a new study, I show that the reverse is also true. Knowing someone is good or bad shapes if we think they are one of “us” or one of “them”. In other words, partisans project their own political identities onto people they view as good, and project the political identities of their opponents onto those they dislike.

Who do Darth Vader and Cinderella vote for?

The first part of the study involved a social experiment that applied a political twist on a childish game. In a representative survey of thousands of respondents from both the US and UK, participants were shown images of fictional characters. These were heroes like Harry Potter and Spiderman, or villains like Scar from Disney’s The Lion King and Joffrey Baratheon from Game of Thrones.

Participants were then asked to guess each character’s political affiliation. What emerged was a striking pattern: participants thought that heroes voted for the same party as them, and that villains voted for the opposing party.

Essentially, US Democrats consistently thought Harry Potter and his friends Ron and Hermione voted Democrat, whereas Republicans consistently thought they voted Republican. Similar behaviour was expected of heroes (and the opposite of villains) from across a whole host of characters from different film and fiction.

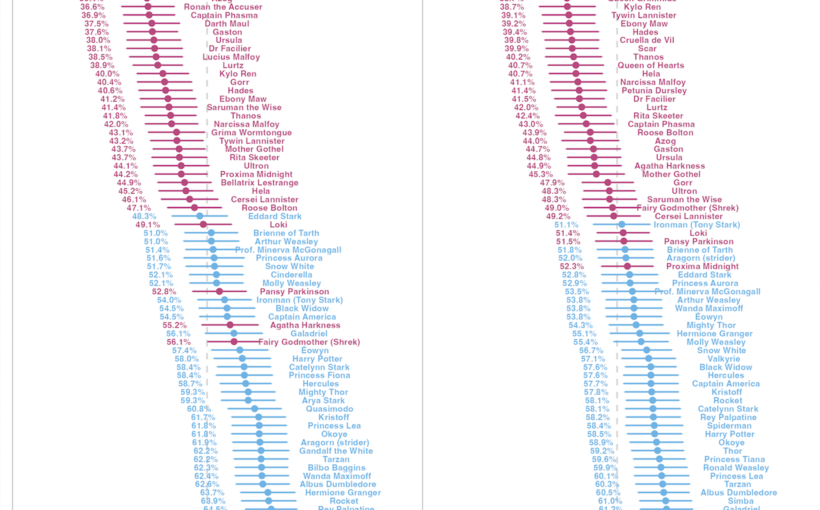

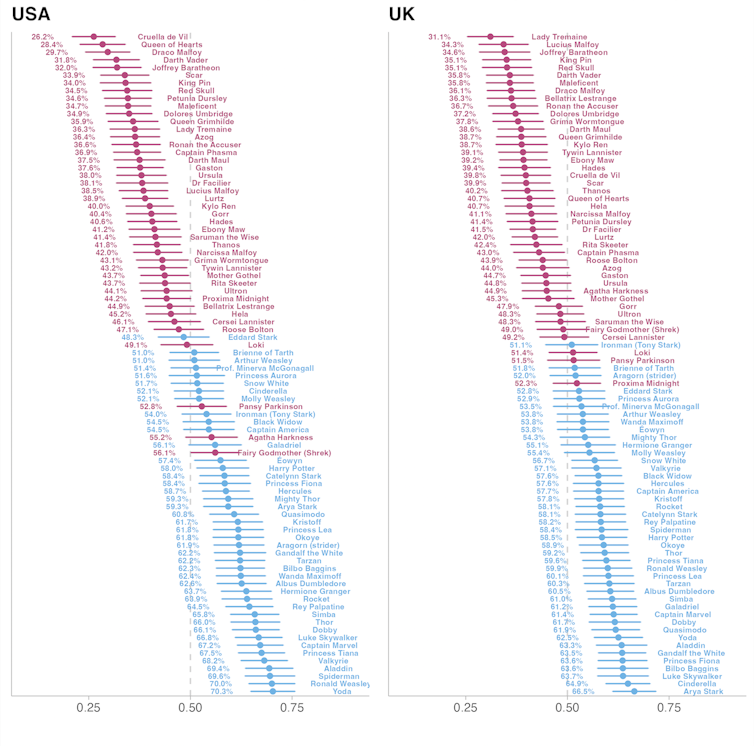

Percentages who thought each character voted for ‘their’ party:

Participants thought Spiderman, Cinderella, Yoda, Aladdin, Brienne of Tarth, Gandalf and Captain America shared their political views. They dismissed Kylo Ren, Ursula the sea witch, Cersei Lannister and Thanos as siding with their political opposition.

Participants were also asked to read a short story about a local politician. In one version of the story, the politician was depicted as a generous figure who donated money to charity. In another, the same politician was shown in a negative light, and as having been accused of corruption. At no point in the story was the partisanship of the politician mentioned.

Despite the absence of any direct mention of partisanship, respondents falsely “remembered” the politician’s party affiliation in a way that aligned with the moral tone of the story. Labour-voting participants who read the generous politician story said they remembered it was about a Labour politician. Conservative-voting participants reading the same story said they remembered it being about a Conservative politician. The reverse pattern was observed among participants who read the corrupt politician story.

These results are striking. Even when there is nothing to be remembered and participants could say that partisanship wasn’t part of the story, voters read what they wanted between the lines based on their own tribal political identities.

These studies demonstrate that partisan identities undermine voter rationality. Politically motivated projection – assuming those who are good must be one of “us” and those who are bad must be one of “them” – doesn’t just shape how we view others; it reinforces and consolidates partisan divisions.

If we assume the person who lives next door is a lousy neighbour because they vote for our political opponents, and simultaneously assume the person who lives down the street votes for our political opponents because they are a lousy neighbour, then we very quickly fall into a scenario where our politically tribal instincts feel increasingly justified.

This cycle of political villainisation deepens divides, making it harder to find common ground. If we continue to let partisanship shape not just how we vote but how we see each other, we risk turning those who don’t share our political views into our enemies.

![]()

Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte has received funding from the British Academy and the Leverhulme Trust