Will the next human to walk on the Moon speak English or Mandarin? In all, 12 Americans landed on the lunar surface between 1969 and 1972. Now, both the US and China are preparing to send humans back there this decade.

However, the US lunar programme is delayed, in part because the spacesuits and lunar-landing vehicle are not ready. Meanwhile, China has pledged to put astronauts on the Moon by 2030 – and it has a habit of sticking to timelines.

Just a few years ago, such a scenario would have seemed unlikely. But there now appears to be a realistic possibility that China could beat the US in a race that America, arguably, has defined. So who will return there first, and does it really matter?

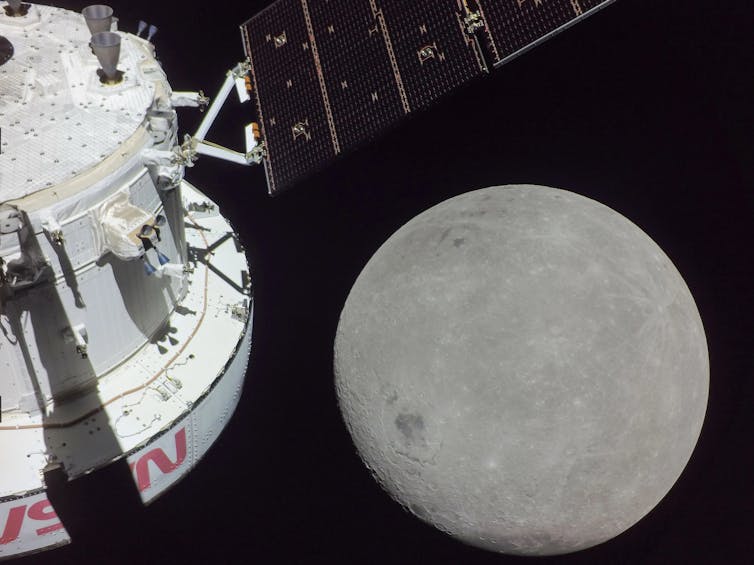

Nasa’s Moon programme is called Artemis. The US has involved international and commercial partners to spread the cost. Nasa set out a plan to get American boots back on lunar soil over the course of three missions. In November 2022, Nasa launched its Orion spacecraft on a loop around the Moon without humans aboard. This was the Artemis I mission.

Artemis II, scheduled for late 2025, is similar to Artemis I, but this time Orion will carry four astronauts. They will not land; this will be left for Artemis III. For this third mission, Nasa will send a man and the first woman to the lunar surface. Though as yet unnamed, one of them will be the first person of colour on the Moon.

Artemis III was scheduled to launch this year, but the timescale has slipped several times. A review in December 2023 gave a one in three chance that Artemis III would not have launched by February 2028. The mission is currently slated to happen no earlier than September 2026.

Meanwhile, China’s space programme seems to be moving at speed, without significant failures or delays. In April 2024, Chinese space officials announced that the country was on track to put its astronauts on the Moon by 2030.

It’s an extraordinary trajectory for a country that launched its first astronaut in 2003. China has been operating space stations since 2011 and has been ticking off important, challenging firsts through its Chang’e lunar exploration programme.

These robotic missions returned samples from the surface, including from the lunar far side. They have tested technology that could be crucial for landing humans. The next mission will touch down at the lunar south pole, a region that attracts intense interest because of the presence of water ice in shadowed craters there.

This water could be used for life support by a lunar base and turned into rocket propellant. Making rocket propellant on the Moon would be cheaper than bringing it from Earth, making lunar exploration more affordable. It is for these reasons that Artemis III will land at the south pole. It’s also the planned location for US and Chinese-led bases.

On September 28 2024, China showed off a spacesuit, to be worn by its Moon walkers, or “selenauts”. The suit is designed to protect the wearer against extreme temperature variations and unfiltered solar radiation. It is lightweight and flexible. Is it a sign of China already overtaking the US in one aspect of the Moon race? The company manufacturing the Artemis Moon suit, Axiom Space, is currently having to modify several aspects of the reference design given to them by Nasa.

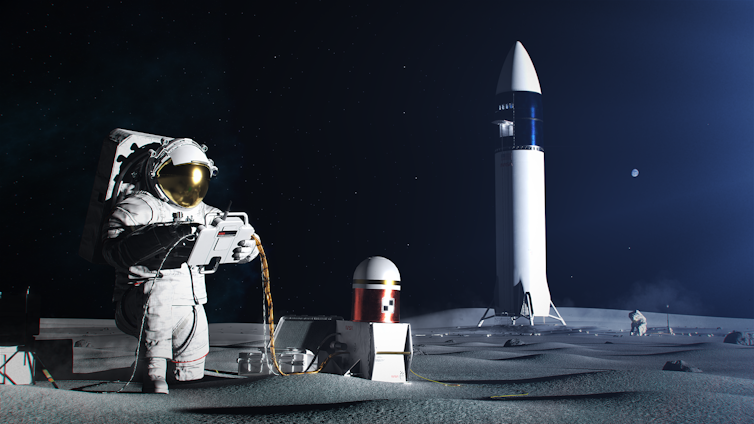

The lander that will carry US astronauts from lunar orbit to the surface is also delayed. In 2021, Elon Musk’s SpaceX was given the contract to build this vehicle. It is based on SpaceX’s Starship, which consists of a 50m-long spacecraft that launches on the most powerful rocket ever built.

On October 13 2024, Starship scored a successful fifth test flight. But several challenging steps are required before the Starship Human Landing System can carry astronauts down to the lunar surface. Starship cannot fly directly to the Moon. It must refuel in Earth orbit first (using other Starships that act as propellant “tankers”). SpaceX needs to demonstrate refuelling and conduct a test landing on the Moon without crew before Artemis III can proceed.

In addition, during Artemis I, Orion’s heat shield suffered considerable damage as the spacecraft made the high-temperature return through Earth’s atmosphere. Nasa engineers have been working to find a remedy before the Artemis II mission.

Too complicated?

Some critics argue that Artemis is too complex, referring to the intricate way in which astronauts and Moon lander are brought together in lunar orbit, the large number of independently operating commercial partners and the number of Starship launches required. Depending who you ask, between four and 15 Starship flights are needed to complete the refuelling for Artemis III.

Former Nasa administrator Michael Griffin has advocated a simpler strategy, broadly along the lines of how China expects to accomplish its lunar landing. His vision sees Nasa relying on traditional commercial partners such as Boeing, rather than relative “newbies” such as SpaceX.

However, simple is not necessarily better or cheaper. The Apollo programme was simpler, but at almost three times the cost of Artemis. SpaceX has been more successful, and economical, than Boeing in sending crews to the International Space Station.

New technology is not developed through simple, tried approaches but in bold endeavours that push boundaries. The James Webb Space Telescope is highly complex, with its folded mirror and distant position in space, but it allows astronomers to peer into the depths of the universe as no other telescope can. Innovation is especially crucial bearing in mind future ambitions such as asteroid mining and a settlement on Mars.

Does it matter whether the first 21st-century selenauts are Chinese or American? This is largely a question about the relationship between governments and their citizens, and between nations.

Democratic governments depend on public support to safeguard funding for expensive, long-term ventures – and prestige is an important selling point. But prestige in a 21st-century Moon race will be earned by doing it well, not sooner. Rushing back to the Moon could be costly, both financially and in the risk to human life.

Governments must set an example of responsible behaviour. Peace, inclusivity and sustainability should be guiding principles. Going back to the Moon must not be about dominion or superiority. It should be a chance to show that we can improve on how we have previously behaved on Earth.

![]()

Jacco van Loon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.