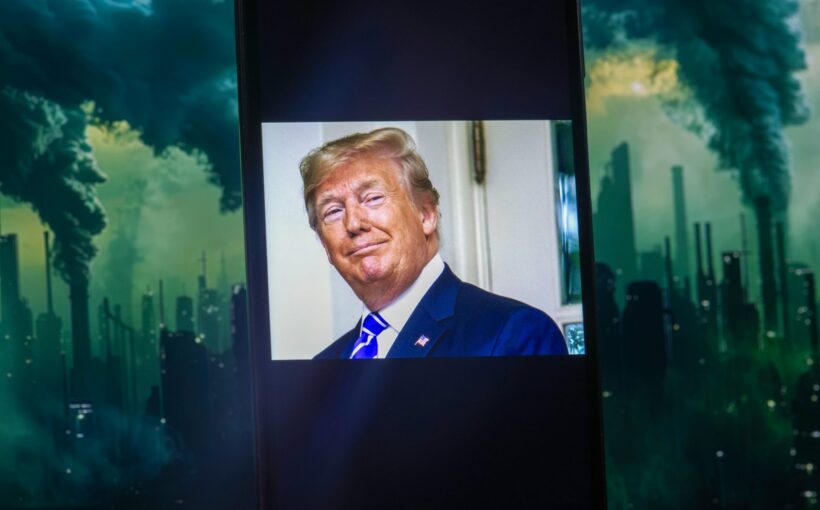

Climate scientists are probably among those most aggrieved by Donald Trump’s return as US president.

Trump has scoffed at the increasingly dire warnings of these scientists and declared his enthusiasm for digging up and burning the coal, oil and gas that is overheating Earth. His empowerment of the far right dims prospects for collective solutions to collective problems, but what is he likely to change about US climate policy?

This roundup of The Conversation’s climate coverage comes from our award-winning weekly climate action newsletter. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 40,000+ readers who’ve subscribed.

Trump has not published a climate agenda. To discern his impact on domestic and international policy, we have to sift through statements, appointments to political positions and the record of his first term.

Here, our academics glean grim portents for the years ahead – and some continuities with supposedly pro-climate presidents of the past.

1. It’s still ‘drill, baby, drill’

Trump’s three-word campaign slogan, “drill, baby, drill”, is intended to sum up his plans for the US oil and gas industry. It’s also an apt summary of existing US energy policy.

Since 2008, when Democrat Barack Obama was elected, oil production has soared from a 50-year low of 6.8 billion barrels a day to 19.4 billion in 2023.

“The United States is already producing more crude oil than any country ever,” says Gautam Jain, an energy and finance expert at Columbia University.

“Oil and gas companies are buying back stocks and paying dividends to shareholders at a record pace, which they wouldn’t do if they saw better investment opportunities.”

Read more: What Trump can do to reverse US climate policy − and what he probably can’t change

2. We won’t always have Paris (or even Rio)

Trump withdrew the US from the 2015 Paris agreement on the first day of his second term (it took him six months to do it last time).

Jain frets that he may go further and exit international negotiations entirely, by rescinding his country’s membership of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, which was adopted in Rio de Janeiro in 1992.

Rejoining would be “nearly impossible”, Jain says, as a future president would need the consent of two-thirds of the Senate.

The US risks dropping the mantle of climate leadership on China, he adds. A recent analysis by Oxford economists Matthew Carl Ives and Natalie Sum Yue Chung suggests that that ship may have sailed years ago.

“China already processes most of the clean energy supply materials and has an advanced manufacturing base that is more capable of scaling up production to meet the rising demand,” they say.

3. The bucks stop here?

A US retreat from international climate diplomacy would afflict people who are particularly vulnerable to the mounting crisis in Earth’s atmosphere. Jain highlights how Trump’s predecessor Joe Biden donated several billions of dollars more towards renewable energy and adaptation in the developing world, compared with Trump in his first term.

However, a 2023 study that estimated each country’s “fair share” of this climate finance pot according to income, population size and historical emissions, issued this withering assessment while Biden was president:

“Based on these metrics, we found that the US is overwhelmingly responsible for the climate finance shortfall,” says environmental economist Sarah Colenbrander (University of Oxford).

“The world’s largest economy should be providing US$43.5 billion of climate finance a year. In 2021, it gave just US$9.3 billion – a meagre 21% of its fair share.”

Read more: China is already paying substantial climate finance, while US is global laggard – new analysis

4. Biden’s green tax credits may endure…

Trump could keep some Biden-era investments in clean energy (tax breaks for investors in renewables, for example) as the benefits are accruing in Republican states, Jain says.

He may still cut tax credits for people buying electric vehicles, though. This would slow the transition from combustion-engine transport by making it harder for people to afford an EV. (Biden’s 100% tariff on Chinese-made EVs hasn’t help either).

Read more: History says tariffs rarely work, but Biden’s 100% tariffs on Chinese EVs could defy the trend

5. … but his methane tax probably won’t

Jain predicts that the greatest damage inflicted by Trump will be to the regulation of fossil fuels and emissions. In his crosshairs is a federal charge for the release of methane from oil and gas wells and pipelines.

Biden identified cutting methane emissions as a potential brake on the accelerating pace of global heating. That’s because methane is a greenhouse gas that lingers in our atmosphere for decades instead of centuries like CO₂ and is far more potent in trapping heat during that time.

Reducing methane emissions could reduce climate change quickly – a climate action lifeline we will be sorry to see thrown away.

Read more: COP26: a global methane pledge is great – but only if it doesn’t distract us from CO₂ cuts

6. The nuclear option

Trump seems to have a soft spot for one low-carbon energy source: nuclear power. Perhaps because civil nuclear maintains the skills and supply chains needed for its military applications?

Read more: Military interests are pushing new nuclear power – and the UK government has finally admitted it

7. Up is down, left is right

Democrats may regret making “trust the science” their dividing line against Trump.

Eric Nast, an environmental governance expert at the University of Guelph, tracked how the first Trump administration altered language on US government websites.

He expects Trump to disguise his regulation bonfire as “strengthening transparency” (blocking air pollution standards that rely on private health data) and championing “citizen science” (dismissing academics from advisory boards for private citizens rich in time and money, who might benefit from scrapping rules and limiting scrutiny).

Read more: 3 ways Trump’s EPA could use the language of science to weaken pollution controls

8. Fighting fire with money

Tesla’s Elon Musk, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg attended Trump’s second inauguration. Their presence – plus a pointed farewell speech by Biden – has provoked murmurs of “oligarchy”: rule by people whose immense wealth and influence has utterly captured ostensibly democratic societies.

At the still-raging LA fires, an oligarch-friendly response to climate change has presented itself: firefighters-for-hire.

“As public firefighters struggle to cope, affluent residents and businesses have turned to private firefighting services to protect their properties,” says Doug Specht, a University of Westminster geographer.

Read more: The rise of firefighters-for-hire exposes the inequality of climate-driven disasters

9. Arctic relations

What explains Trump’s sudden interest in the Arctic? Oil, gas and critical minerals newly liberated by thawing ice in a region warming four times faster than the global average says engineer Tricia Stadnyk at the University of Calgary.

“The second Trump administration is aware of both the new opportunities and risks as global temperatures shatter new records and thresholds, and an ice-free Arctic becomes a possibility,” she says.

Read more: Climate change is fuelling Trump’s desire to tap into Canada’s water and Arctic resources

![]()