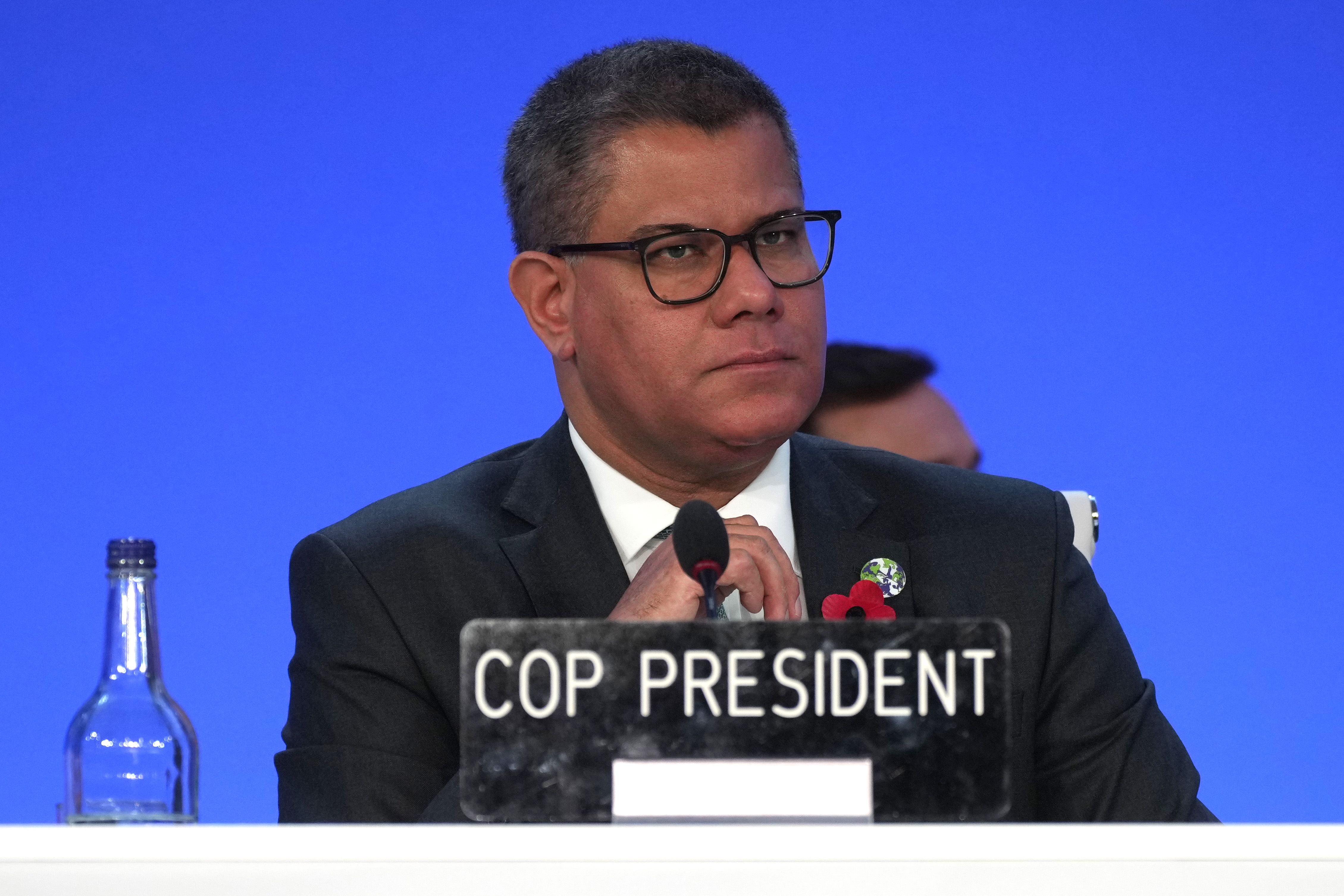

Draft pledge calls on world to ditch coal quicker, step up emissions cuts

A published draft of the Glasgow agreement includes language acknowledging that the world should be aiming to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees, which could be a first step in obliging countries to make more ambitious pledges to reduce greenhouse gas emissions over this decade.

The document, published on Wednesday, is not final and COP26 delegates from nearly 200 countries will now negotiate the details over the next few days.

Consensus from all nations is required for the final text, and if agreed, the language would be the first strong acknowledgment that 1.5 degrees is the limit the world should aim for.

READ MORE: Even with big new promises, world still on track for devastating warming

The most notable line is that the draft urges signatories to come forward by the end of 2022 with new targets for slashing emissions over the next decade, which scientists say is crucial if the world wants to have any chance of keeping warming below 2 degrees and closer to 1.5.

David Waskow, director of the International Climate Initiative with the World Resources Institute, welcomed the 2022 target as progress.

"So this is crucial language because it does set the timeframe around when countries need to come forward with strengthened targets in order to align with Paris," he said, referring to the 2015 Paris Agreement, which set a global warming limit of 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels, with a preference for 1.5 degrees.

Although that was agreed six years ago, many parties' emissions plans do not align with that goal.

Mr Waskow warned there were "certainly parties who have been pushing back on that," naming Saudi Arabia and Russia.

READ MORE: Australia ranked last on climate policy in major international report

CNN had reached out to those countries on the same issue on Tuesday and was seeking new comment.

China has publicly said several times it would oppose a shift from 2 degrees to 1.5.

Typically draft COP agreements are watered down in the final text, but there is also a chance that some elements could be strengthened.

The agreement includes soft language like "urges" and "recognises" around emissions cuts, so does not have the same force of a treaty like the Paris Agreement, but has some legal basis.

But on the whole, the language builds on the Paris Agreement and includes lines on the importance of speeding up the phase-out of coal and other fossil fuels, although no specific dates are mentioned.

READ MORE: Australia's most wanted fugitive arrested

The Australian piece in the puzzle

There is no plan in place for Australia to phase out coal mining or export and the country's negotiators are expected to push back on any pledge to phase it out.

Australia, along with the US and China, did not join some other major polluters in a promise agreed last week at COP26 to phase out their use of the heavily polluting fossil fuel.

Industry, Energy and Emissions Reduction Minister Angus Taylor said Australia was an "active and constructive participant" in the negotiations.

"Between 2005 and 2021, Australia's emissions fell by 20.8 per cent, outpacing the reductions of the United States, Canada and New Zealand, and every other major commodity exporting nation in the world," he said, in a statement.

Australia pledged to hit net zero carbon emissions by 2050 but did not increase its 2030 target beyond a 26 to 28 per cent cut, although Prime Minister Scott Morrison projected a 35 per cent reduction.

The nation — along with Brazil, Indonesia, Russia, and several other countries that did not increase their targets — would be expected to submit new goals by November 2022 if the drafted Glasgow statement was agreed to.

READ MORE: Rain bomb to smash multiple states with flood warnings in place

Vulnerable countries push for stronger language

WRI's director of climate negotiations, Yamide Dagnet, said it was climate-vulnerable countries that pushed for the stronger language, but what they wanted was for the agreement to set stronger obligations for particular nations.

They are also seeing the 2022 goal as difficult for them to achieve without a bigger boost in funding.

"For them, it's going to be very difficult … to come back home and to say, after all of your efforts … you have to do another adjustment effort within a year," she said.

There is an extensive section on the issue of climate finance, which is the key sticking point in talks.

A dynamic has emerged at the negotiations where developing nations are demanding that rich nations honour a pledge they made more than a decade ago to transfer US$100 billion a year ($136 billion) to the Global South by 2020, and start paying for "loss and damage".

That means holding them financial liable for the impacts on their countries, acknowledging rich nations' historic role in the climate crisis.

READ MORE: Mum's tribute to twin girls killed in Byron Bay house fire

https://twitter.com/cnni/status/1458086981284421632

The draft agreement notes that the US$100 billion goal will likely be met by 2023, three years later than promised, although it includes several points to encourage a faster mobilisation of money.

The language is fairly weak in that it doesn't set earlier targets to come up with the funding.

"On one side of the scales, it advances a detailed process for accelerating climate mitigation goals, but, on the other side of the scales, on finance and loss and damage, it is fuzzy and vague," said Mohamed Adow, director of climate think tank Power Shift Africa.

"The missed deadline for the $100 billion promise doesn't get acknowledged — and this is a key ask from vulnerable countries."

Tracy Carty, Oxfam's head of delegation at COP26, said "support for loss and damage cannot be left to random acts of charity."

"We need a robust finance system in place and new sources of support for countries suffering from loss and damage that goes beyond humanitarian aid," she said.

"There are four days left and there's everything to play for to ensure Glasgow is remembered for the right reasons."

What the agreement says on 1.5 degrees

On 1.5 degrees, the document says it "recognises that the impacts of climate change will be much lower at the temperature increase of 1.5 degrees compared to 2 degrees and resolves to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees, recognising that this requires meaningful and effective action by all Parties in this critical decade on the basis of the best available scientific knowledge."

It "also recognises that limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees by 2100 requires rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions, including reducing global carbon dioxide emissions by 45 per cent by 2030 relative to the 2010 level and to net zero around mid-century."